Post-train a Model to Fish

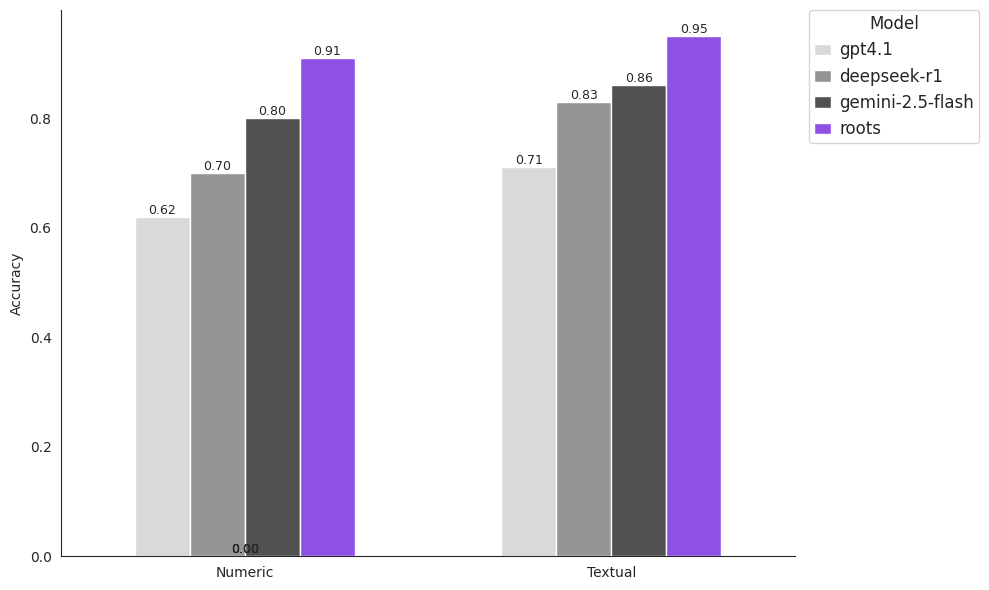

We demonstrate how a specialized 25B parameter Mistral model, post-trained on domain-specific data, can outperform Google's Gemini 2.5 Flash by double-digit margins on insurance loss run extraction tasks.

A Practical Benchmark

Consider that a language model is deployed by a large company to perform a task. Consider that this task is conceptually simple, but requires the application of thousands of rules to complete accurately. Consider that this task has to be performed every minute, on varying inputs. If you had to do this task (and could read extremely fast), would you read the thousands of rules every minute, along with the input? More likely, you would memorize the rules and apply them from memory. There are many practical, non-coding business problems that can be solved by language models as they exist today, but foundation models need to use, essentially, a list of thousands of rules to solve them effectively. Some of these rulesets can be supplied in-context, but for the most difficult problems, prompting becomes unmanagebale given context length limits. And besides, giving the model such a ruleset every time would be like giving the model a fish so it is fed for a minute. But as the adage suggests, we choose to post-train the model to fish—to encode these rules into the weights of the model. We show that a 25B parameter Mistral model post-trained on data laboriously curated for such a task can beat Google’s brand-new Gemini 2.5 Flash (which likely has orders of magnitude more parameters) by a double-digit accuracy margin on a realistic business use-case benchmark.

We evaluate model performance on a single task, similar to the one imagined above: creating JSON representations of long, complex, and highly variable unstructured input documents (insurance loss runs from our model’s test set). Each model receives the same prompts, besides model-specific tokens, to ensure evaluation parity. We summarize performance with the metric cell-wise accuracy, which represents the proportion of cells the model gets correct. We separate extracted cells into two bins: Numeric, for numeric cells that must obey various accounting relationships, and Textual, for text cells that must obey strict formatting rules.

o

Roots’ post-trained loss runs model wins by a substantial margin on these aggregated metrics. This result poses questions about what kind of models we should be seeking to train. As foundation models become increasingly smart, become able to do math and populate their context with “reasoning,” they will not magically gain particular domain knowledge about the specific industries in which they are deployed. Being good at math doesn’t equate to understanding accounting practices, for example. Should a generally intelligent model exist, one wonders how it would approach solving loss runs extraction or any other difficult task. If we define intelligence against ourselves, against the strategies we would take in solving this problem, we might expect a smart model to train a smaller, specialist model on accurately labeled loss runs data—but this is exactly what we do today.

o

Roots’ post-trained loss runs model wins by a substantial margin on these aggregated metrics. This result poses questions about what kind of models we should be seeking to train. As foundation models become increasingly smart, become able to do math and populate their context with “reasoning,” they will not magically gain particular domain knowledge about the specific industries in which they are deployed. Being good at math doesn’t equate to understanding accounting practices, for example. Should a generally intelligent model exist, one wonders how it would approach solving loss runs extraction or any other difficult task. If we define intelligence against ourselves, against the strategies we would take in solving this problem, we might expect a smart model to train a smaller, specialist model on accurately labeled loss runs data—but this is exactly what we do today.

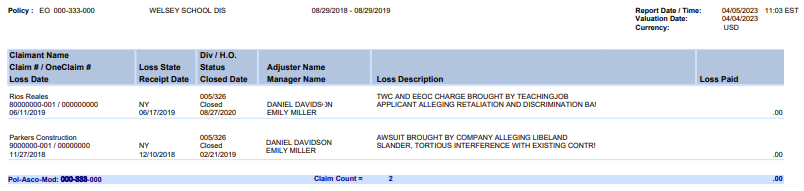

In the business automation space, loss run extraction is considered a difficult problem, due to the extreme length of the tabular output and the complexity of the underlying documents. Moreover, in an automation context, we don’t have the benefit of lenient evaluation metrics like pass@k accuracy—stochasticity and sampling are not helpful, since there is only one way to represent a particular loss run with our data model. We need to be able to deterministically extract data across the entire distribution of loss runs, in one pass, and at a high degree of accuracy. In many cases, for example OpenAI’s o-series models, temperature and other sampling parameters cannot be set by the user. These restrictions make post-training and hosting open-weight models all the more attractive. But beyond these concerns, creating a unified data model for the space of loss runs poses its own challenges. Understanding a loss run can take experienced insurance underwriters upwards of twenty minutes. Consider this section of a fictional loss run:

This section represents two claims made on a given insurance policy during a given time period. Some loss runs might contain hundreds of such claims, over several different policies and time periods. The model is tasked with understanding each claim during each time period as individual rows, as well as reporting information about the policies as wholes over these time periods. It’s important that, between all the individual claims and their aggregations at the policy level, the books balance.

As we see, the tables that represent this information can be quite complex. In this case, we have a sort of three-dimensional table: column names are actually column lists, and correspond to lists written in individual cells. This representation is not necessarily common, but is frequent enough that an effective model needs to understand it. As the table becomes longer, and as the cells become less and less proximal to the column headers they correspond to, the columns headers that enable parsing become more difficult for models to remember simply in-context. When we post-train, however, remembering and using these patterns becomes native to the model.

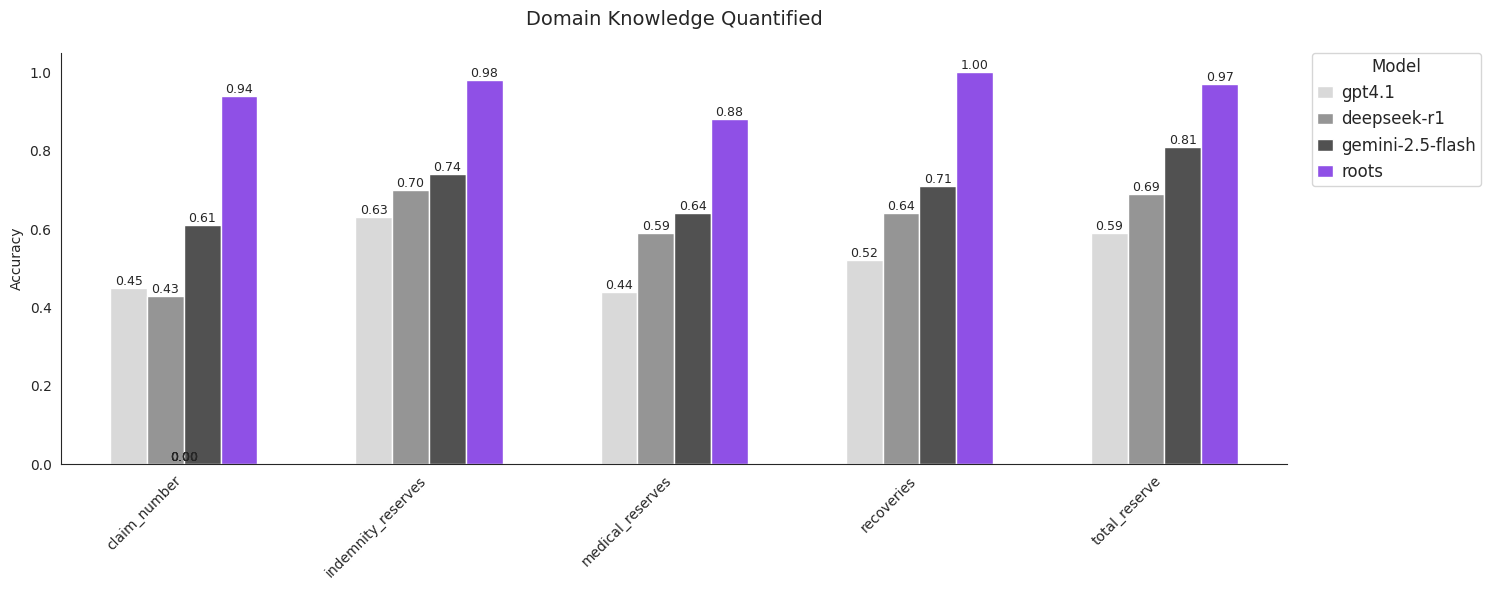

Looking deeper into some particular cell types where our specialist model excels, we start to see the importance of domain knowledge. The claim_number field, for example, requires a precise extraction following company specific formatting, since these claim numbers are used to collate data in downstream industry systems. The fields indemnity_reserves, medical_reserves, recoveries, and total_reserve are likely to require arithmetic using accounting practices that change across insurance companies and lines of business (auto, property, etc.). These challenges are not complex in concept, but they are highly particular.

Could this domain knowledge problem be solved in-context by a truly general intelligence, especially as big AI labs look to increase the context length of their models? It might be the case that all insurance knowledge can be distilled into a (likely several) thousand page “textbook,” which can then be supplied to a generally intelligent model along with the extraction problem. Feeding this many tokens to massive model for each generation does not seem economical. As the results presented here demonstrate, foundation models do not understand the domain of insurance well and would be ineffective at creating this textbook, so human experts would be necessary. Moreover, this context space is highly valuable—if we were to post-train a model with a long context window, we would be able to provide few-shot examples to the model in the context saved by not prompting the model with our textbook. But even outside of these practical concerns, the task seems fundamentally unsound. All of the rules that would comprise our textbook are already encoded in the data and its labels. Why would we decode these rules back into English, just to feed this text to a language model which re-encodes it? Instead, we choose to harness the power of neural architectures to learn these rules natively from the post-training data.

Challenges Solved by Specialized Post-training

We can think about a model’s degree of specialization as what is in-distribution for the model. As we have seen, there exist realistic business use cases that out-of-the-box models fail to solve satisfactorily. This fact raises a question: while solving these difficult industry problems, how much of these models’ training data is useful for the task at hand? Some time ago, we at Roots hypothesized that, if we were to winnow down what we consider in-distribution and focus on creating clean training data for this distribution, we can post-train small models to solve specific challenges.

Generation Length

Across our datasets, the average generation length models are asked to produce is 4491 tokens. As the model begins to generate, the original prompt (which also contains the loss run the model ingests) is pushed out of the model’s context length, and performance subsequently degrades. While a naive document chunking approach can help to ease this context problem, the model then loses contextual information in sections of the original document that have been excluded from the current chunk. Then, encodings of real contextual understanding, or domain knowledge, must exist within the model weights themselves to achieve high performance.

Output Format

To further help with the generation length problem, we use a list-of-lists output table format, as opposed to list-of-dicts, to avoid generating keys for every row and thus save on generated tokens. We can think of list-of-lists as csv-like, in the sense that the first list is always a list of column names. If we input the above loss run segment into our model, we would expect:

[

[

"Claim - Accident Description",

"Claim - Accident State",

"Claim - Allocated Expense Reserves",

"Claim - Allocated Expenses Paid",

"Claim - Carrier",

"Claim - Claim Number",

"Claim - Claim Reported Date",

"Claim - Claimant Closed Date",

"Claim - Claimant Name",

"Claim - Date of Incident",

"Claim - Indemnity Paid",

"Claim - Indemnity Reserves",

"Claim - Line of Business",

"Claim - Medical Reserves",

"Claim - Nature of Injury",

"Claim - Paid Medical",

"Claim - Policy Number",

"Claim - Policy Year",

"Claim - Recoveries",

"Claim - Status",

"Claim - Total Incurred",

"Claim - Total Paid",

"Claim - Total Reserve",

"Claim - Claim Type"

],

[

"Lawsuit brought on behalf of student onallegations of disability discrimination and failure to pro",

"TX",

"",

"",

"AIG",

"501-776684-001 / 6193796588US",

"03-12-2020",

"02-22-2022",

"Diego Perez",

"03-10-2020",

"",

"",

"E&O",

"",

"",

"",

"EO 0016156210-029-000",

"2019",

"",

"Closed",

"0",

"0",

"",

""

],

[

"Lawsuit brought on behalf of student onallegations of disability discrimination and failure to pr",

"TX",

"",

"",

"AIG",

"501-776688-001 / 1802209165US",

"03-12-2020",

"02-22-2022",

"Jennifer Guerrero",

"03-10-2020",

"",

"",

"E&O",

"",

"",

"",

"EO 0016156210-029-000",

"2019",

"",

"Closed",

"0",

"0",

"",

""

]

]

In subsequent lists, we identify which field a value belongs to by its index. The list-of-dicts representation, on the other hand, requires that each row has both field names and values. As the outputs become longer, the additional length incurred by list-of-lists’ extra row becomes negligible relative to list-of-dicts’ keys that are generated for every row. However, this token-efficient representation poses additional challenges for models not trained to write these long tables—keeping the column indexing clear is a form of domain knowledge itself. The complexity of this output table structure is a significant factor in GPT-4.1’s lackluster performance on this benchmark, as it failed to produce valid JSONs a surprising number of times.

Basic Math

Training a language model to do math reliably requires substantial compute, but while building our model we found that basic arithmetic reasoning can be achieved, at least by proxy, in our specialized context using simple pattern matching—a task that a small non-reasoning model excels at. Across the distribution of possible documents our model might receive, numbers are reported in variable ways. We might want to extract numbers A, B, and C. Let’s say that there exists the relationship A + B = C. Some of our documents report A and B, others report B and C, and so on. To provide a true structured rendering of the document, we would like to fill in the gaps and calculate this missing number. We achieve this parameter- and compute-efficiently by teaching the model to write “” and then C is computed using post-processing. While the model is restricted from performing arithmetic directly, it uses attention to leverage the structure provided by its specialized, domain-specific task, and achieves its goal without having to waste tokens or complicate the output by generating reasoning. We see below that Roots’ model achieves comparable accuracy to out-of-the-box models, including a reasoning model in DeepSeek-R1, on these cells which are likely to require calculation.

Data is Difficult

The most significant impediment to post-training is data. Coding and math problems have easily verifiable solutions, so when we ask an LLM to integrate a function, we can numerically integrate to check the model’s output. However, unlike math problems, many of the most difficult industry use cases involve data that’s private and highly protected—and moreover requires industry specific expertise to understand and annotate correctly. Even with expert annotators and access to data, enforcing annotation consistency across training samples is difficult and requires several rounds of cleanups. We use a cross-validation technique to do so, where we post-train a model on half of our training set, test on the other half, and vice versa, in order to ensure agreement. This level of consistency is what allows, for example, the model to exhibit quantitative reasoning skills using simple attention mechanisms and pattern matching. After many iterations of this cleaning process, we are able to create a model that achieves state-of-the-art performance on a specialized problem that arose out of real industry needs.

Conclusion

A rising tide lifts all boats, but it doesn’t lift the sky. As stronger foundation models become available, so do stronger base models. Data curation and post-training pipelines will continue to elevate performance on difficult tasks, and can themselves be improved with advancements in, for example, reinforcement learning and cleverness in how training sets are constructed. Consider the story of the development of this loss runs model: many months ago, we were training a 7B Mistral model to compete with GPT-4.1, and we were winning. Evidently, superior models were released by Google and DeepSeek that beat OpenAI’s offering. But at the same time, open-weight models improved, and Mistral released a 25B offering, elevating the performance of our post-trained model beyond the best out-of-the-box models in the space. Even holding base models constant, there is substantial performance yet to be gained from improving our own data curation and training processes—the cross validation mentioned previously is only the lowest hanging fruit here.

So post-training wins, but for how long? As training algorithms evolve, as parameter counts and compute increase, can this paradigm of specialization for hard problems hold? It might be the case that a true general superintelligence can attain the same performance or better as our 25B parameter post-trained model, but at a very high cost. In any case, wouldn’t the intelligent thing for that model to do be exactly what we as humans are doing? That is, to post-train a smaller model that can do the job, and efficiently.

Appendix

Cell-Wise Accuracy

We show the formula for the cell-wise accuracy metric, where N is the number of samples (tables extracted) and n is the number of cells in an extraction row.

$$ CW = \frac{1}{N} \sum_{i=1}^{N} \frac{1}{n_i} \sum_{j=1}^{n_i} \text{Acc}(cell_{i,j}) $$

Full Benchmarking Table

| field | category | deepseek-r1 | gemini-2.5-flash | gpt4.1 | roots |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| indemnity_paid | Financials | 0.83 | 0.74 | 0.65 | 0.95 |

| total_incurred | Financials | 0.52 | 0.71 | 0.66 | 0.74 |

| recoveries | Financials | 0.64 | 0.71 | 0.52 | 1 |

| paid_medical | Financials | 0.74 | 0.74 | 0.44 | 0.86 |

| medical_reserves | Financials | 0.59 | 0.64 | 0.44 | 0.88 |

| indemnity_reserves | Financials | 0.70 | 0.74 | 0.63 | 0.98 |

| total_paid | Financials | 0.85 | 0.93 | 0.67 | 0.78 |

| total_reserve | Financials | 0.69 | 0.81 | 0.59 | 0.97 |

| allocated_expenses_paid | Financials | 0.84 | 0.93 | 0.86 | 0.93 |

| allocated_expense_reserves | Financials | 0.55 | 1.00 | 0.76 | 1 |

| claimant_name | General | 0.90 | 0.94 | 0.80 | 0.94 |

| date_of_incident | General | 0.89 | 0.94 | 0.80 | 0.94 |

| claim_reported_date | General | 0.89 | 0.82 | 0.83 | 0.93 |

| claim_number | General | 0.43 | 0.61 | 0.45 | 0.94 |

| line_of_business | General | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.76 | 1 |

| carrier | General | 0.88 | 0.93 | 0.75 | 1 |

| policy_number | General | 0.81 | 0.91 | 0.65 | 0.99 |

| policy_year | General | 0.94 | 0.99 | 0.78 | 0.99 |

| status | General | 0.88 | 0.68 | 0.57 | 0.99 |

| accident_state | General | 0.90 | 0.98 | 0.88 | 0.96 |

| claimant_closed_date | General | 0.89 | 0.85 | 0.72 | 0.94 |

| accident_description | General | 0.60 | 0.77 | 0.54 | 0.78 |